The Rocket Boys of Hollywood’s “October Sky”

September 16, 2016You might know the movie “October Sky” about a group of small-town Southern West Virginia boys who dream of becoming rocket scientists. But did you know that there’s an entire festival celebrating their story and legacy?

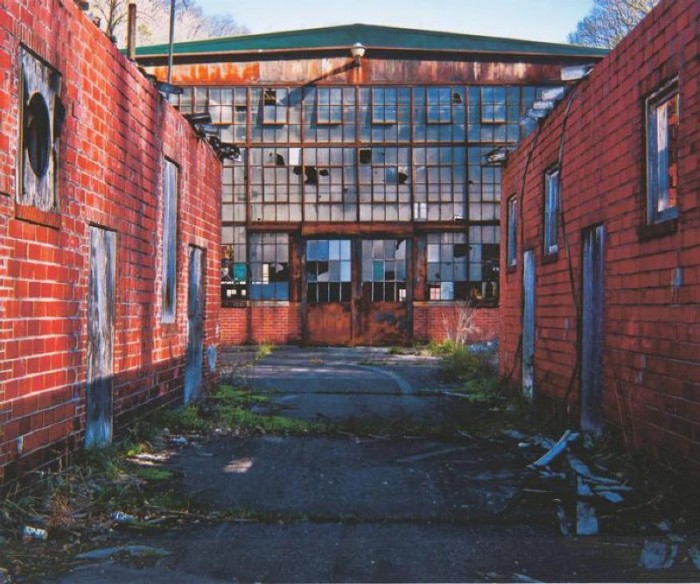

Coalwood is a small McDowell County town. Needless to say, it owes its name and very existence to the mineral that lies underneath it, but the coal mine closed in 1982.

Like many coal towns of Southern West Virginia, Coalwood is “down in the holler”— surrounded by steep hills on all sides. Folks have quipped that towns like this are so deep in the holler that “the sun comes up at 10 in the morning, and goes down at 3 in the day.” There’s not a lot of sky to look up at.

But looking to the sky is exactly what 6 teenage boys did in Coalwood back in 1957.

But looking to the sky is exactly what 6 teenage boys did in Coalwood back in 1957.

This was the year that the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the world’s first artificial satellite. Though it wasn’t even 2 feet in diameter, Sputnik struck fear and apprehension into the hearts of many Americans. We had been beaten into space by our Cold War adversaries!

Talk of Sputnik even reached Coalwood. Homer Hickam, Jr., remembers that the entire town would turn out on clear nights to stare into the sky for a glimpse of the spacecraft. More specifically, Hickam and 5 friends, all around 14 years old at the time, became obsessed with rockets and space travel.

This was something new; the dawn of the Space Age had come to their little neck of the woods. Hickam later recalled this in a short story for Smithsonian’s Air and Space magazine, which expanded into the memoir Rocket Boys, later into the movie October Sky: “All our fathers worked in and around the mines, as had their fathers and grandfathers. Before Sputnik, we were headed for the mines too. Now, suddenly, we were looking in a different direction: up.”

In 1957 rocket and missile technology was still very new, and mostly in the realm of government agencies and top-level scientists in special laboratories. Model rockets were not a thing yet, and plans for them did not exist like they did much later, in magazines or on the internet. Hickam and his friends Roy Lee Cooke, Jimmy Carroll, Quentin Wilson, Sherman Siers and Billy Rose wanted to build rockets in Coalwood, but were pretty much on their own.

After briefly looking over some plans for a rocket in Life magazine, the “Rocket Boys” filled a large flashlight casing with gunpowder from cherry bombs— and blew up Hickam’s parents’ fence.

Most teenagers would probably be satisfied with having made something explode. But the Rocket Boys were just getting started. Over the next 3 years, they would experiment with different rocket bodies and propellants (usually made from different chemicals from the mine that Hickam’s dad supervised). They also established a makeshift launchpad for their rocket projects, which by this time they were calling the “Big Creek Missile Agency.”

Most teenagers would probably be satisfied with having made something explode. But the Rocket Boys were just getting started. Over the next 3 years, they would experiment with different rocket bodies and propellants (usually made from different chemicals from the mine that Hickam’s dad supervised). They also established a makeshift launchpad for their rocket projects, which by this time they were calling the “Big Creek Missile Agency.”

They stopped being just kids with fireworks, and moved towards actual science, math and engineering. As Hickam wrote, “Until Sputnik, we had been indifferent to science and math, neither seeming to have much to do with our future.” But— much to the surprise of their teachers— the Rocket Boys started incorporating principles of Newtonian motion, thrust, trigonometry and fluid dynamics into their experiments.

In 1960, 3 years into their project and fresh from a trip to the National Science Fair, the Rocket Boys launched their final rocket, the Auk XXXI (named for an extinct bird that was ironically unable to fly). By this point, the entire town of Coalwood had gotten behind the Big Creek Missile Agency, and everyone turned out to see the launch. The 5-foot tall, electrically ignited rocket climbed to an altitude of 4 miles.

Hickam would go on to work as a NASA engineer, and later an author. 3 of the other Rocket Boys also became engineers. All of them graduated college, and none followed their fathers into the mines.

Today, the tale of the Rocket Boys is one of West Virginia’s best-known stories. Hickam’s memoir is assigned in high school classes throughout the state.

West Virginia kids face a lot of challenges today: an economy in transition away from coal, a shrinking population and even some broad national stereotypes about rural Appalachia. They need to remember that it is possible even for kids in the smallest, most isolated towns to dream big, and aim for the stars.

"Not only is there a working coal mine, but the museum on the mine grounds actually has a small planetarium.”

Equally important: Hickam and his friends realized that the community of Coalwood and Southern West Virginia was behind them— encouraging and not hindering. Though not all the Rocket Boys live in West Virginia today, they maintain strong ties to the state.

West Virginia has been keeping the legacy of the Rocket Boys alive in one really cool way: with a the Rocket Boys Festival. For its first 14 or so years, the “October Sky” festival actually took place in the little hamlet of Coalwood. Hickam attended every year to sign books and mingle with model rocket builders from all over the nation.

In 2012, the October Sky festival moved to the bigger city of Beckley to accommodate the crowds, and changed its name to the Rocket Boys Festival. (Fun fact: “October Sky” is an anagram of “Rocket Boys.”)

“I’d interviewed Homer when I worked for the radio station WTNJ,” said festival director William Scott Hill. “He was sold on moving the festival to Beckley, especially when the city let us have it at its Exhibition Coal Mine. Not only is there a working coal mine, but the museum on the mine grounds actually has a small planetarium.”

Coal and sky– the combination was perfect, and the festival has been here ever since.

The Rocket Boys festival has grown and expanded a lot since its origins as a rocket enthusiasts’ convention. This year, there will be scholarships, essay and rocket contests, screenings of iconic West Virginia films, an acting workshop with actor Chad Lindburgh of October Sky and other films, and a writing workshop with the man himself, Homer Hickam.

The Rocket Boys festival has grown and expanded a lot since its origins as a rocket enthusiasts’ convention. This year, there will be scholarships, essay and rocket contests, screenings of iconic West Virginia films, an acting workshop with actor Chad Lindburgh of October Sky and other films, and a writing workshop with the man himself, Homer Hickam.

Hickam and other Rocket Boys, all in their 70s now, are all over the festival each year. This year he, Roy Lee Cooke, Jimmy O’Dell and Billy Rose will field questions at a screening of October Sky.

If there is one thread that ties this festival together, and connects it to the Rocket Boys’ story and the state of West Virginia, it is that it “shows the next generation pathways to success,” in the words of Hill. Homer Hickam was audacious to think that a small-town kid from Appalachia could wind up at the forefront of Cold War-era aeronautics. For that matter, he was audacious to leave his job as a NASA engineer to pursue writing. But he was successful.

As young folks from Appalachia and beyond come to learn about rocket science, writing, acting and more, they’ll also see West Virginia for what it was, what it is and what can be. The story of Hickam and the Rocket Boys, spanning from Sputnik to NASA to Hollywood to high school classrooms across the state, is the story of West Virginia.

We can still embrace the hollers while looking to the stars.