Trace fall along the old rail lines

September 15, 2016Want a perfect combination of natural beauty and West Virginia history? Check out Southern West Virginia’s railroads during the fall.

For more than 150 years, Southern West Virginia’s transportation system has been an intertwined network of rivers and railways— water and steel. The rivers carved natural highways through our rugged mountain country, and later, railroads followed these routes (or in the case of the Virginian, ignored them completely.) Together, this intersection of the industrial and the natural gives us a fascinating perspective of the Mountain State.

Railroads were the key to our complex mountain terrain, and connecting us to industrial centers to the north and west. Winding trails of steel carried coal and timber from the mountains to the river valleys of the Ohio River, and to the coastal ports of Virginia.

The booming glory days of coal and timber may be over, but the railroads remain. And we think our fascinating network of railroads are the best ways to explore— maybe even better than West Virginia’s famed country roads.

There’s no better time of year to take in the natural beauty than when our stunning forests explode in hues of gold and red. Days are still warm enough for t-shirts and jeans, and nights cool enough to start burrowing down into the warmth of quilts and down comforters.

If you want to experience a bit more of Southern West Virginia railroad culture, scenery and history, it is awaiting you in beautifully preserved depots, regional festivals, and even special tours through some of Appalachia’s finest scenery.

Thurmond

Thurmond

A good bit of our region’s railroad experience is centered around the New River Gorge.

An active freight and passenger rail line traverses the bottom of the gorge in its entirety. Its deepest section around the town of Fayetteville, the impressive Highway 19 bridge, and a world-class whitewater run, contains minimal railroad history beyond solitary tracks and ruins of old coaltowns that have been mostly consumed by the dense forest.

Above this section, though, the gorge gets a bit wider and the river gets more calm. Here you’ll find a handful of charmingly preserved railroad stations.

The small town of Thurmond is a must-see. After a remote drive on a 1-lane blacktop road, you’ll get to this isolated railroad depot. Despite its small size (population 5, as of the 2010 census), Thurmond is still an incorporated town. In fact, just last year, Thurmond became the smallest town in the U.S. to enact an anti-discrimination ordinance— everyone is welcome in this gorge-ous hamlet!

Take a walk through the main section of town— a railroad on one side; old structures of a bank, city hall, store, and train station on the other; fall foliage in all directions above; the river rumbling away below.

It’s hard to believe that this used to be one of the most booming towns in the gorge at the turn of the century.

In fact, the town was even locked into a sort of rivalry with some very rowdy neighbors. Thurmond was actually established as a “dry” town without alcohol in the days before prohibition, but just across the New River was the infamous Dunglen Hotel, a true party spot with alcohol, gambling, big band music and mining high-rollers.

Today, you’ll likely be Thurmond’s only visitor, especially as the fall days become shorter and cooler.

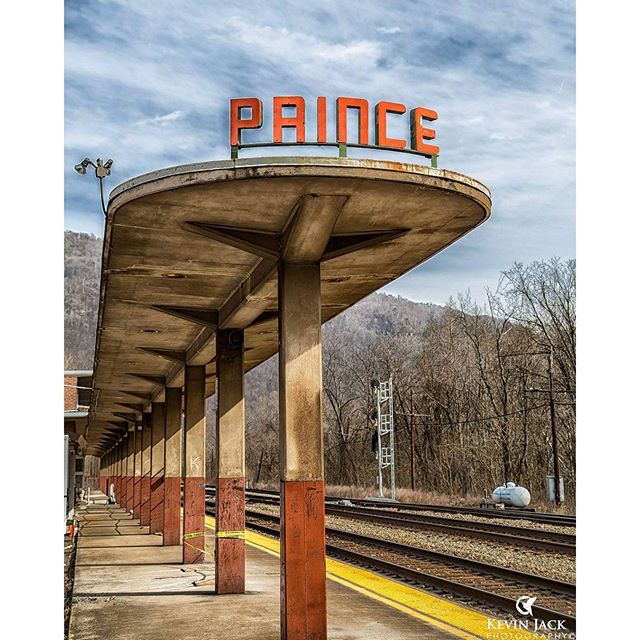

Prince

Prince

Up the river from Thurmond a dozen miles or so is Prince, another historic railroad depot. Prince is still an active railroad hub, just as it has been since the 1870s, when the C&O Railroad intended for it to be a major hub on a route from Washington D.C. to Cincinnati. Passengers of the Amtrak line at Prince can still walk over the engraved logo of the old C&O Railroad’s mascot “Chessie” the sleeping kitten on the station’s floor.

The Prince station, a beautiful red brick structure from the 1940s, was actually ahead of its time. It was built to take advantage of what architects today call “passive” heating and cooling. Its south-facing glass panes are designed to be in the shade during the summer, but to collect sunlight during the winter when the sun is lower.

Prince is a great spot to book a quick trip on a passenger train, and is the main stop for train travelers going to the recently-completed Summit-Bechtel Boy Scout Reserve. If you want to catch the full beauty of the New River Gorge in the fall, an Amtrak trip from Prince to Montgomery is a great way to go.

Hinton

Several miles upstream from the Gorge is the town of Hinton. Though it’s small, Hinton is the largest population center along the New River in West Virginia— actually, this County Seat of Summers County is arguably the only real town along the New in the Mountain State!

Hinton also has a long history as a natural crossroads, situated near the confluence of the New River with 2 of its major tributaries: the Greenbrier from the northeast, and the Bluestone from the southwest It is also the point where the CSX railroad leaves the New River to head east along the Greenbrier.

Hinton is proud of its railroad history and culture. Train buffs should definitely check out the town’s railroad museum any time of the year. A great time to visit Hinton is in the fall, specifically over the weekends of Oct, 15-16 and 22-23 for their annual Railroad Days festival.

Hinton is proud of its railroad history and culture. Train buffs should definitely check out the town’s railroad museum any time of the year. A great time to visit Hinton is in the fall, specifically over the weekends of Oct, 15-16 and 22-23 for their annual Railroad Days festival.

Railroad Days is a great fall festival. Every year is different, but there’s always live music, regional arts and crafts for sale, and lots of great food.

But the coolest thing about Railroad Days might very well be how you can get there: by train. New River Train Excursions operates train trips for these 2 weekends from Huntington all the way up the New River Gorge to Hinton, just in time to catch the best of the festival.

Railroad history abounds on this expedition, from Huntington’s beautifully restored depot at Heritage Station to the industrial landscape of Charleston to the impressive engineering of the railroad through the gorge itself. Book a trip for Saturday, Oct. 15, and you might even catch sight of BASE jumpers parachuting off of the New River Gorge Bridge in Fayetteville nearly 1,000 feet above you.

All in all, it’s about 4 hours to get to Hinton, 4 hours to check out the festival and another 4 to return. You will definitely not forget a fall day like this.

Princeton

William Nelson Page was an engineer, coalman, and geologist who helped survey the New River railway in the 1870s. Much later, around the turn of the century, he envisioned a new railroad route that would connect West Virginia’s southern coalfields not to the Ohio River Valley, but to the booming Virginia sea port of Hampton Roads.

Bigger railroads did not want the competition of such a direct, lucrative line, but Page was fortunate to have wealthy Rockefeller affiliate Henry Rogers as a financial backer. The resulting 1907 Virginian Railway was expensive; unlike almost all other railroads (including the New River Train), it avoided river valleys, and just audaciously tunneled through some Appalachia’s roughest country.

“This was one of the most expensive railroads in the world, but it paid off,” said Pat Smith, director of the Princeton Railroad Museum. It had a more direct line to the Atlantic, and a very long, easy downhill grade through Virginia.

Princeton boomed: the Virginia Railroad was headquartered here, and they built a foundry to produce train parts here. Booker T. Washington even made a series of speeches along the railroad, encouraging his philosophy of hard work and industry.

Princeton boomed: the Virginia Railroad was headquartered here, and they built a foundry to produce train parts here. Booker T. Washington even made a series of speeches along the railroad, encouraging his philosophy of hard work and industry.

Even after the Virginian Railroad was merged with the Norfolk & Western in 1959, its course remained the major route for Southern West Virginia Coal. The final coal train passed through Princeton only last year.

To catch a bit of this fascinating history, check out the Princeton Railroad Museum. Not only will Smith share plenty more regional history, but you’ll also be treated to rare newspaper clippings of train wrecks in the area, a restored switchboard and (most popular) a fully restored caboose.

Actually, the caboose is not 100% historically accurate, Smith confessed.

“We don’t have a hole in the bathroom floor,” she said. “Cabooses back then did not have tank toilets; just a hole that emptied directly onto the tracks!”

Now you know.

Nature lovers can see our gorges and rivers by train, and railroad history buffs will certainly be impressed by the wild, wonderful backdrop of our depots and lines. Check out our mountain rails in the fall time, and you’ll surely come away smitten by our nature and our history.